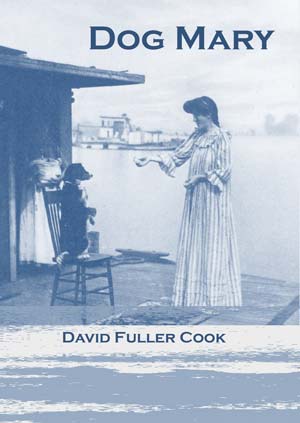

Dog Mary

by David Fuller Cook

Dog Mary is the story of Mary Bass, a legendary woman said to have come to the aid of the homeless and poor of the Great Depression. speaks to the nature of suffering, hatred, and prejudice, yet Zora Purefoy and Mary Bass – strong, independent women – lend to the novel the greater truth of brightness of the human spirit and the strength of heart-felt relationship.

First Chapter

The character of Dog Mary was inspired by Carl Bogardus’s boyhood story of a shantyboat woman, Tammershams, whose pack of more than twenty dogs was slaughtered by the townspeople of Warsaw, Indiana during the 1920s.

The Legend

John Finch talked about Dog Mary like she was religion. Maybe she was, for him.

“It takes heart and soul to see her, Daniel,” he told his son when he was a boy. Daniel would watch the sparkle of life in his father’s eyes as John Finch spread his fingers toward the surface of the river. “She lived here on this river; she loved it. She still sings in the wind. Whisper her name in a breeze, Daniel, and she’ll come to you, help you if you need her.”

Daniel would listen. Sometimes he believed he could hear her. Other times he felt he was but another of his father’s disappointments. John Finch seemed to grow grayer, darker-souled and more bitter as he got older. Daniel watched him come home night after night from the cotton mill, at suppertime sit behind a dark wall of silence at the head of the table. When he talked about Dog Mary though, Daniel saw something come to life in the ashes of his father’s eyes.

As a boy, Daniel never thought much about it, the man his father was when he was young, the dream he had for life. Daniel only knew that his father’s life wasn’t the life he had planned for himself. John Finch had gone into the Navy during World War II, stationed in the Pacific where his right leg had been crushed by a jeep when it fell off the jack as he was changing a tire in the sands of New Guinea. He had returned from the War and gone to work in the cotton mill.

“Happy?” he said to Daniel. “It doesn’t matter what anybody tells you, if they tell you, they’re lying: ain’t nobody happy. Less than one man in a million gets to do what he wants to do and you can get used to anything.”

It wasn’t often John Finch felt hopeful enough to tell them, but when he told his Dog Mary stories to Daniel and his younger brother Joshua it was usually after dinner, along with stories of growing up in the Great Depression in a tough section of Memphis called Little Egypt. Dog Mary was a shantyboat woman, a white woman, cut from a different cloth, living in hard times too painful to remember when the hard times were done. She had kept a mongrel pack of dogs following her every step of the way she walked. In his telling of her their father freed himself from his worries and his fears, but always, the next day, the man Daniel and Joshua thought of as their father returned.

“Mary had all kinds of dogs,” John Finch told them, “loners and throngers, rebels, rakes and refugees, thieves, beggars and diplomats, the flea-bitten and the beaten. She’d walk into Patesville, that long-lanky walk of hers, accompanied by that pack of dogs, like the Pied Piper of Hamlin followed by his rats. There was Bus, who always had Mary’s hand when he wanted it, but she’d throw her arms around the lot of them, or work her way through them, like Jesus on the mount. They all found their purposes with Mary. Each of her dogs was named and every dog had his or her part, like an angel or patron saint. Tanker protected smaller boys from bullies; Linus stole rich men’s shoes off shoeshine stands for those who were barefooted; Mollie the spaniel fed the hungry, once brought an entire uneaten Christmas dinner to a shantyboat family practically starving. Trombone knew when and which doctor to go to for medicine; Augie could find lost children and lead them home; Zofie saved men, women and children from drowning.”

But for all he told his two boys about the river and about Dog Mary, John Finch didn’t like them going down to the river to play. He thought of the river as having a will. “She decides on the living and the dead,” he told them. “If the river takes a mind to it, she’ll up and kill you quick. Few received into her waters ever rise again.”

To make his point he’d tell a story of a man who jumped into the languorous waters of the river to fetch a puppy who had jumped overboard. A massive creosote telephone pole slammed into him and he sank like a pallet of bricks. The seething Mississippi had inexplicably swept another man off the deck of a fishing boat, his bloated body found two weeks later fifteen miles down river below Wyanoke. John Finch made sure his boys knew about the suicidal souls who had jumped off the Frisco or Harahan Bridge, or when cane-pole fishermen lost their footing and slipped in, and especially when people who could swim got swept away and drowned. John Finch didn’t want his sons to underestimate the nature of the river, the dangers that lurked in snags, whirlpools, snarled trotlines and cottonmouths. He said a current, neither good nor bad, could rise unforeseen from the moving bulk of a river and take you when you least expected it.

The days of childhood marched on, but Daniel often stayed in bed in the morning, listening to his father getting up, his mother silently fixing his father’s breakfast. Daniel lay there in the dark, waiting for the cotton mill whistle to blow, for his father’s chair to scrape across the kitchen’s wood floor and to hear his father putting on his clothes to go out the door to work. Daniel watched him come home night after night. It wasn’t just a lunch pail he carried home from the cotton mill. It was worry; it was despair. It looked like death to Daniel.

On Saturdays John Finch put in a half-day’s work at the cotton mill and then worked on house projects—the car, a busted hot water heater, a ceiling fan—and Daniel and Joshua were left to wondering what drove their father to work so hard. John Finch awoke early on Sundays too, to attend an eight o’clock service. Their mother rarely went, and Daniel and Joshua, knowing their father wanted them to go to church with him, would lie in bed and pretend to be asleep. Sometimes their father woke them up anyway. The boys knew their father kneeled on the hard wood floor and prayed every night by his bed before he slept. They had watched him through the cracked door from the darkened hallway. As a child Daniel had no idea what his father was praying for.

On Sunday afternoons, John Finch would take his boys down to the chain-link fences of the shipyards along the Mississippi River, walking with an almost imperceptible limp, but more apparent when he was tired. It was quiet down there on Sundays. He would expound on the various kinds of ships and how boats were built or what repairs the men were making, the inner workings of those boats laid out on the bare ground as though they were giant toys spilled from a toy box: propellers, enormous steel plates, pipes, hoses and compressors, hawsers, shafts and boilers. Some hulls were hoisted by winch or crane onto metal stanchions where they would receive fresh paint as though for Christmas morning, their machinery in the process of being cleaned and sanded, while others lay aside, rusting and neglected, their hulls hove over, continually forgotten. Maybe John Finch intended to inspire his boys with grander dreams than what his dreams had become, but it was Joshua who would join the Navy, rather than go to college, as Daniel did. But by the time Daniel went away to the university he had built a wall between himself and his father.

They argued. Daniel was involved in a peace coalition, protested the killing of the four Kent State students and the bombing of Cambodia during the Vietnam War. Religion, politics and anger separated them. Daniel didn’t believe there was anything John Finch knew that needed knowing. He had freed himself of his father, until that day his father died of a heart attack.