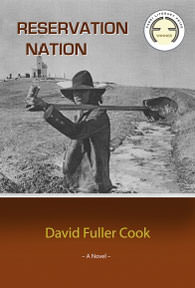

Reservation Nation

by David Cook

My first work of fiction, Reservation Nation, was the winner of the first Francis Fabri Literary Prize and has received praise from the LA Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday. Powell Books kindly said that I was “one of the most promising new talents in the South.”

First Chapter

Down Reservation RoadMy name is Warren Eubanks, the Seed; I am Uwharrie. No one told me I was Uwharrie until I was eleven years old. I thought I was Indian but didn’t know that being Indian was more than not being white, that truth is more than what’s not a lie.

The main road on the Old Reservation was a dirt road called Reservation Road. It was one way in and one way out, a dead-end road. I lived near the top of that road with Grandmother and Grandfather in a house my grandfather built. If I hadn’t’ve lived with them I would have been adopted or something, like my sister Ruby, or sent to Indian boarding school the way many kids were, because my mom and dad got killed in a car crash.

When I was a kid our fathers and mothers were not talking about continuing to be Indian and many of the old people weren’t saying anything, and I guess mostly a lot of people were trying to figure out how not to be an Indian, and my father had been the chief of that. I didn’t know until later the reason for the blue smoke around him. Back in the fifties there were some on the Reservation who were for termination. They were saying that if they had the deeds to the land they lived on, then they could improve their homes. They were fed up with being wards of the federal government and wanted to pay their taxes like everybody else so they could hold their heads up and look the world in the face. They said they didn’t like it, Chief Billy dressing up in his furry head gear, like a Sioux or something, in a Christmas parade, but Chief Billy was always willing to do it, what he called furthering our interests and getting the white people to do things for us.

There was a lot of not-saying on the Reservation when I was a kid. I learned it. I had to unlearn it, because I knew there was something nobody was talking about. I could feel it. But I didn’t know if it was true because I was a kid. I felt silence where words or laughing or crying were meant to be.

“That is your Owl medicine,” Aunt Ida said to me. “You feel what nobody says, even to themselves. If they never say it they never know why they lived. You have known this immediately for a long time.”

She meant that the knowledge came from the time of our ancestors, when we emerged as a distinct culture, as a people.

“I can’t tell you much more than that,” she said. “Women don’t have to do anything special, if we stay off alcohol. We’re pretty much accessible anyway, but in the old days young men would go off alone–no food, no water–and sit by themselves. Women don’t have to do that. It’s easier for us, but then, life is harder.”

I don’t think Aunt Ida would have told me this except, by this time, my father had gotten himself drunk and killed in a car crash, and maybe it was an accident and maybe it wasn’t, but he wouldn’t be asking me at supper, “What is this bullshit about an owl?”

There’s a lot I don’t remember about my mom, and memories I’ll never have, but there was some kind of disagreement between my mom and my grandmother. I don’t know what it was. Maybe it was because Mom didn’t do much, or didn’t try as hard as Grandmother wanted her to. Mom never took up the weaving, and it seemed like the only words shared between them were those they had to say.

“Your mother was a very strong woman, in her own way,” Aunt Ida told me when I asked her about it.“ Your mother just knew what to do.”

Aunt Ida lived at the top of the mountain in the next to the last house on Reservation Road. Aunt Ida was my great aunt; even when I was a boy she was old. She tied her hair back in a cloud-white bun, had a sharp nose like a hawk, and eyes like a hawk too. She knew what you were doing all the time. She could read minds; she could read mine anyway. She had a particular way with dogs, another way with chickens, and another way with horses or cows. She had words in the old language that was a way of speaking with them, but I never got the chance to really learn them.

I remember when I was a kid, one day after school, we were pitching hay into the hay loft and Aunt Ida said to me, “Warren, the cow doesn’t like you and Joe Bad Crow throwing rocks at her.”

Sometimes Aunt Ida would chain the cow. I’m not sure why she did this, because mostly she let that old cow wander anywhere she liked. That cow never went far. She liked Aunt Ida. All the animals did. But one day Joe Bad Crow and I found out Aunt Ida had chained the cow and so we snuck up on her, like we were great hunters, and threw rocks at her, knowing she would chase us. But she had that chain around her neck. We knew she’d run out of chain. We thought we were being brave.

“How do you know we were throwing rocks at the cow?” I asked her. “Did you see us?”

“No.”

“Who told you then?”

“She did,” Aunt Ida said, still pitching hay. “She wanted me to ask you to stop throwing rocks at her.”

That was all she said. The next time Aunt Ida chained the cow Joe was ready to head out to the field where that cow was and throw rocks at her but I told him what Aunt Ida had said.

“What does she know?” Joe said. But we didn’t throw rocks at the cow anymore.

Aunt Ida said small birds were bright thoughts, said that if a person was having trouble with negative thoughts they could keep their eye out for small birds and that would help them: tanagers and redbirds, field buntings most people never notice, sparrows too, for their happy movements.

Sun Susie, Aunt Ida’s niece, worked the early shift at the hospital. I think Sun Susie got her love of horses from Aunt Ida. Before she got married Sun Susie lived with Aunt Ida, and even after she got married she always helped with the chickens and cows, but what she really loved was horses. Sun Susie loved horses more than anyone I’ve ever known, and she believed one day that she would move away from the Reservation for good and it would be because one of her horses won at the races. One of her horses was going to win at Red Rock or Lansdale and then everything would just get better. Maybe that horse would even win the Kentucky Derby or something. It never happened though. She was all her life waiting for a winner. Usually there were four or five horses she’d have at one time, but none of them ever won anything. Sun Susie would get home from her job at the hospital, in the middle of the afternoon, watch a soap opera on her TV and then she’d be out working those horses until dark and then get up and do it again. Sun Susie just kept putting her money into horse feed and keeping care of them, paying some skinny white man to come over with his truck and trailer and haul one of her horses over to the Lansdale race track once a month and then haul the horse back.

Grandfather said there were a lot of horses in the old days. Sun Susie would have been happier then, not because of the horses really, but because she wouldn’t have had that disease in her blood, the way she was sick with worry, like a lot of white people. Sun Susie wore her hair in a ponytail and smoked those cigarettes. Most of the time she looked worried, older than she was, smoking those cigarettes, drinking a cooler of coffee, and getting dark circles under her eyes. Sun Susie smoked Marlboros. I always thought it was because they had horses in their commercials but Sun Susie said she had been smoking since she was thirteen years old. Her face looked a little bit like a horse. She was pretty but her teeth were big. She was skinny too. Aunt Ida was all the time telling her she should eat more.

“You eat like a bird,” she would say. “Eat up!”

Sun Susie might not eat another bite. She might get up from the table and stomp off. I could see it. I could see the blue smoke. It wasn’t cigarette smoke; it was blue smoke. I didn’t see it so clearly until after the yearling had gotten himself tangled up in the fence. That was a sad thing. Me and Grandfather had come every day to watch at the fence, watching where that young stallion ran up and down. He bucked and threw his head back and snorted at the sky like he was remembering the wild from where he came from. That young stallion was one fine-looking horse, had the heart of ten brave men. The pasture, the whole wide world was his. He was a dreamer and he was dreaming of when he would run the whole wide world.

“He’s a winner,” Grandfather had said. “This is the one Sun Susie has been waiting for. He will make her happy and win many races.”

But that young stallion ran into the barbed wire fence. He must have been running fast because he tore himself up bad. Maybe he was trying to get out. He broke one of the strands of barbed wire and got his leg tangled up. He was ripped up pretty bad because Sun Susie sent for the vet, and horse doctors cost money. It was worse than they thought, tore tendons or something, and that young horse didn’t become the champion he was born to be.

“The world is different now,” Grandfather said. “Sometimes things don’t happen the way they’re supposed to. There didn’t used to be any metal to keep horses from running where they were born to run. There was never supposed to be a barbed wire fence there, and that’s why he couldn’t see it.”

“But isn’t that just the universe balancing itself out?” I said, because this was something Grandfather was teaching me.

“I don’t know,” he said. “That horse is a winner; it’s just that he’s never going to do it at the big-time race track with all the white men with the money come to watch.”

Grandfather told Aunt Ida that Sun Susie should get rid of her horses.

“They’re not happy,” Grandfather said. “If they were happy they would win all the time. If those horses were happy there wouldn’t be one white man’s horse that could beat them. How can they be happy with a fence such as the Kowache have?”

“If there wasn’t that fence those horses would leave,” Aunt Ida said. “Gordon Gannon would probably catch them and say they were his.” It was her way of keeping Grandfather from saying anymore about Sun Susie’s horses. She just wanted Sun Susie to be happy.

Like many on the Reservation, Sun Susie was caught up in forces she didn’t understand. Maybe you could say Sun Susie’s father’s drinking split up her family but that doesn’t say where he got it from; it had all the symptoms of the Kowache disease, the spirit sickness. She sure did love horses though. In Sun Susie’s family there was a tension between the old ways–the words and the stories–and Presbyterianism and the white ways. There were family silences, things unsaid, which broke out in twisted ways, as arguments, bad words and thoughts. Sun Susie’s two brothers grew up in foster homes, and when Sun Susie was in her teens she ran away from her foster home, hitchhiked to Utah, lived with a cousin or something and eventually moved to California. A couple of years later she phoned Aunt Ida, and Aunt Ida bought her a bus ticket home from San Jose. Sun Susie moved back to the Reservation, moved in with Aunt Ida. Maybe Sun Susie had an innate attraction to suffering and that’s why she got killed the way she did, buried somewhere over behind Old Man’s Back. It isn’t directly understood because white people were involved.

OUT OF STOCK

OUT OF STOCK